Neural Network Steganography

Hiding secrets and malicious software in any neural network

- 9 minsIntroduction

We all have secrets, and now you can share these with your favorite neural network 🤫

gaborvecsei/Neural-Network-Steganography - Code and notebooks for the experiments. I encourage everybody to follow the post with the code for easier and more practical understanding.

Steganography is the practice of concealing a message within another message or a physical object [1]. Hiding a message in a picture, or a picture within another picture are good examples on how you can break down the two entities (what we can call base data and secret data) and slightly alter the base to hide your secret. The idea, is that you can make really small modifications to the base which is usually impossible to spot with your eyes and those modifications contain what you wanted to hide.

Imagine increasing every $R$ value from the $(R, G, B)$ representation of the image with $1$ if $R < 255$. The result is a brand new image where you’ve hidden your “secret”, and still you will hardly be able to tell them apart.

The idea is the same with neural networks as a NN can contain millions of parameters which we can smartly modify to embed some secrets. This is what we can read about in the publication “EvilModel: Hiding Malware Inside of Neural Network Models” [2] which I wanted to test with my own implementation.

Floating-Points and how to modify them

In computer science, we are only approximating real numbers as you’d need infinite bits to represent a real number with infinite precision. This is why we are using the floating-point numbers with which we can represent these numbers with a fixed number of bits to a certain precision and range. In this post I will be using the single precision, 32 bit representation (float32), but you could easily extend the theory for representations with more/fewer bits.

Structure of a FP32

I won’t cover the whole story around floating points, there are several well written articles, you can read it up here: [3], but as a quick refresher, this is what you need to know for these experiments. We can split the binary representation into 3 parts and then use these to calculate the value of the number:

- sing ($s$) - the 1st bit

- exponent ($E$) - 8 bits after the sign bit

- fraction ($F$) - 23 bits after the last bit of the exponent

(LSB visualization, source: [3])

Modifying these binary representations allows us to store some data while giving up some precision what we can control by the decision how many and which bits to change in the original bit sequence. The formula to calculate the real number is from which we can see that by modifying $F$ we can do the least harm [6]:

$x = (-1)^s \times (1.F) \times 2^{E-127}$

Floating-Point experiment

As an experiment, let’s say, we would like to modify the number $x=-69.420$. I wrote a little utility class [4] with which we can easily experiment with the representation. Let’s take $x$, convert to the mentioned binary representation: $11000010100010101101011100001010$ and then calculate it’s value again with the formula: $-69.41999816894531$. It’s not the same as the original one…🤔 and yeah that’s the whole point, the difference is $1.8310546892053026e-06$. And kids, this is why we are not doing drugs equality checks with floats.

As another experiment we can take $16bits$ from the fraction of $x$ and play around with it, “simulate” how the value changes as we change these bits. Randomly doing this $1000$ times yields the following plot:

But of course we can just set all bits to $0$s and $1$s and then we have the “range of change”. The wider this range is the more afraid we should be when modifying the NN, as predictions can and will be altered.

You can also experiment more with float32s just run this notebook.

Hiding the secrets in Neural Networks

The process is the following:

- 🔎 Evaluate your NN without any modification on a test dataset

- Store each individual prediction not just the overall metrics (e.g. f1 score) - for more through evaluation

- 0️⃣1️⃣ Convert your data/secret to binary representation

- 🤓 Calculate how many bits are needed to hide this data, then check if you have the available “storage” in your NN

- $storage=\text{nb_bits} * \text{nb_parameters}$

- Remember that there is a quality-quantity trade-off so try to use low number of bits

- 🤖Go over the parameters in the network, convert to binary format, then switch the defined bits to bits from the secret

- 🔎 Evaluate the NN again, and inspect the differences

Quality - Quantity trade-off

There is a trade-off what we need to consider when modifying bits of parameters in a neural network: The more precision you give up at each value the more data you can store. But think about what this precision means in a NN. You are using these parameters to perform the forward pass and receive a prediction, and you’d like to keep this prediction as close as you can to the original one. Worst case scenario, the outputs of the network will be so different, that you won’t notice the 24 days of training what you did.

As a general rule, just try to compress your data and use less bits from the fraction. Empirically it’s better to modify less bits everywhere int he network compared to modify more bits for certain selected layers. I will include such measurements in upcoming posts.

Experiment

After all this theory let’s see an actual experiment 🥳. I wrote the tools to use it not just to sit on it 🦾.

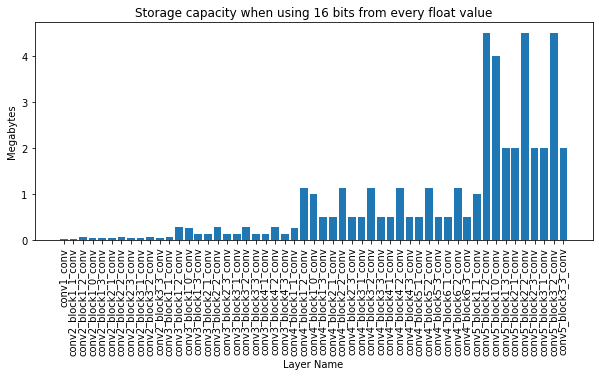

Parameters

I used the well known ResNet50 network trained on ImageNet which is easily accessible at every deep learning framework. But how much data can we store here? Actually… a lot, but it should not be surprising with the number of parameters. After I decided to run the experiment, where I change $16bits$ from the fraction of every parameter (in every Conv2D layer) I could calculate the amount of data I can store. Here you can see the layer-wise breakdown:

Adding up all the bits for the params in the 53 layers, it turns out we can easily store $44MB$s of data. And keep in mind that today this is an averaged size CV model. It would be really easy to hide a few Trojan viruses here [5].

We can also take a look on basic statistics for the parameters, to get a hint how much precision we need to retain, and these would help for any fancier placement of the secret bits (e.g. Calculate the number of bits to use for clusters on values), but I will be using a simple iterative method.

Min: -0.7719802856445312

Abs. Min: 8.192913014681835e-10

Max: 0.9003667831420898

Mean: -0.0007807782967574894

---

Nb total values: 23454912

Nb values < 10e-4: 1486452 - 6.3375%

Nb values < 10e-3: 13138630 - 56.0165%

Nb negatives: 12746193 - 54.3434%

Nb positives: 10708719 - 45.6566%

---

(Maximum) Storage capacity is 44.0 MB for the 53 layers with the 16 bits modification

Placement of the bits

For quick experimentation I chose to generate a random $44MB$ data as a secret and a simple iterative approach for hiding it, where I use a stepping window on the secret bits and starting from the 1st layers 1st parameter I make the modifications. In the first iteration I take the bits from 0th to 15th from the secret, convert the first parameter in the first conv2d layer to the binary representation, take the last 16 bits of the fraction and switch the two. The second iteration I step the window and take it from 16th to 31th and switch with the last 16 bits of the second parameter. And this goes on until we don’t have any more bits to hide.

Reconstruction

So I think the backward process is obvious and I won’t waste virtual paper on it (it’s a homework for everyone reading this 😉), but there are 3 things you need to remember for the reconstruction:

- The order in which you modified the layers and the parameters (now it’s ordered by the index of the layer in the NN)

- The number of bits used for each parameter (fortunately it’s global for this algo)

- The index of the last modified parameter, so we can stop the process

- (If your data is $8 bits$ while your NN has $20,000,000$ parameters, you can hide a single bit in the first $8$ parameters)

Evaluation - How much the predictions changed?

As the test dataset I used images randomly found on my laptop, as we don’t necessarily interested in the predictions, only in the difference of the predictions compared to the original state. You only need to pay attention that the dataset should be diverse enough, so it covers all cases the network can meet with.

With my $14,241$ images the results are the following:

Analyzing the softmax output values with the 1000 classes:

Min abs difference: 0.0

Max abs difference: 0.11202079057693481

Number of changed prediction values: 14240972 / 14241000 | 99.9998%

Looking only at the changes where the prediction label (np.argmax(output)) is different:

Changed number of predictions: 146 / 14241 | 1.0252089038691103%

So we can see that almost all outputs changed slightly, and for some cases (approx. $1\%$) this resulted in a new output label. This is not surprising based on the maximum change values, just imagine a 3 class case where these are the original values: $[0.3, 0.34, 0.36]$ (label would be 2) and after the modification it’s: $[0.3, 0.351, 0.349]$ (where label is 1).

Conclusion

While using a relatively simple approach it is clear that we can use NNs to hide secrets. A lot of secrets… With keeping in mind the introduced trade-offs, and testing of the approaches, we can modify the network while loosing little accuracy.

I think you are already thinking about smarter and more sophisticated approaches, and in a follow up I would like to test those, and evaluate a wider range of models.

References

[1] - Steganography - Wikipedia

[2] - EvilModel: Hiding Malware Inside of Neural Network Models

[3] - Single-precision floating-point format - Wikipedia

[4] - Floating point investigation notebook

[5] - How large is a piece of Malware? - SophosLabs

[6] - Single-Precision Format - ScienceDirect